Finding Becky

Growing up, magazines told me Kate Moss was the epitome of beauty and it made me feel out of place. It wasn’t until a trip to Montserrat that I found myself…

Exclusive | 3 min read

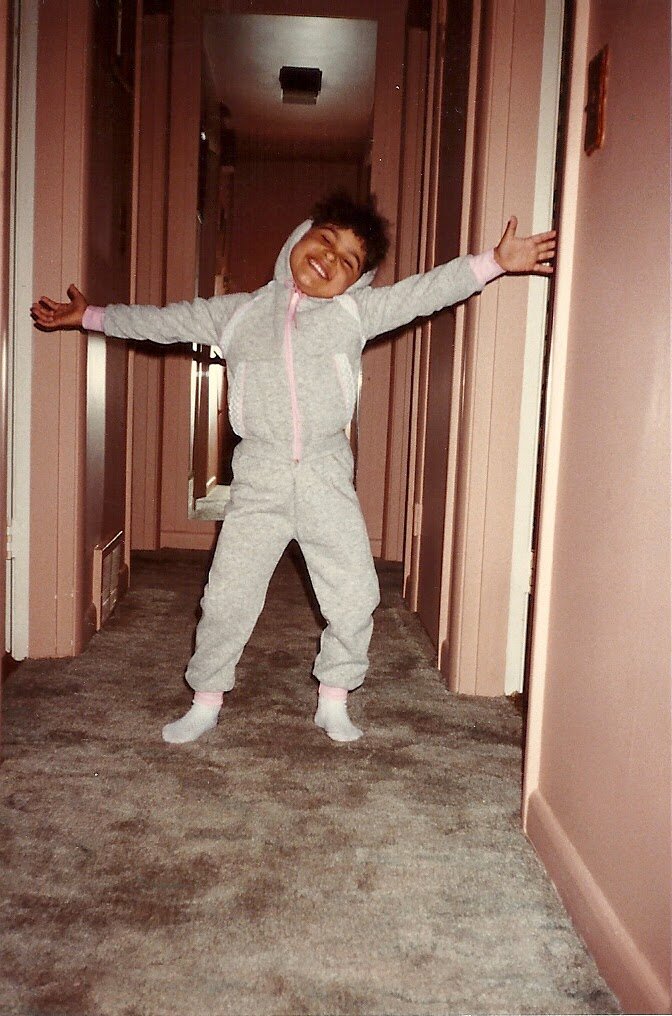

As a mixed raced woman growing up in Britain, it’s fair to say I’ve always felt different from those around me. One of the first times I realised that it was my colour that set me apart was upon overhearing a conversation at a classmate’s birthday party. One of the other mums commented to mine that the school was lovely but the ‘only problem is they’ve started taking a lot of ‘darkies’ now.’ My white mum responded with ‘yes, and one of them is my daughter.’

Whilst I was obviously aware at eight that I wasn't white, until that point I hadn't realised that that would be something that people might consider a negative.

This was just one of many incidents that would take place over the years, from the man in a bar I worked at chanting ‘there’s a n***** in the camp’, to having black people call me a coconut (black on the outside white on the inside - an insult alluding to my mixed heritage). A combination of these comments, and being a young woman in an era where Kate Moss was the epitome of what the magazines said a woman should look like, meant that with my dark hair, full boobs, thick thighs, and big hair, I didn’t feel like I really fitted in.

Singled out

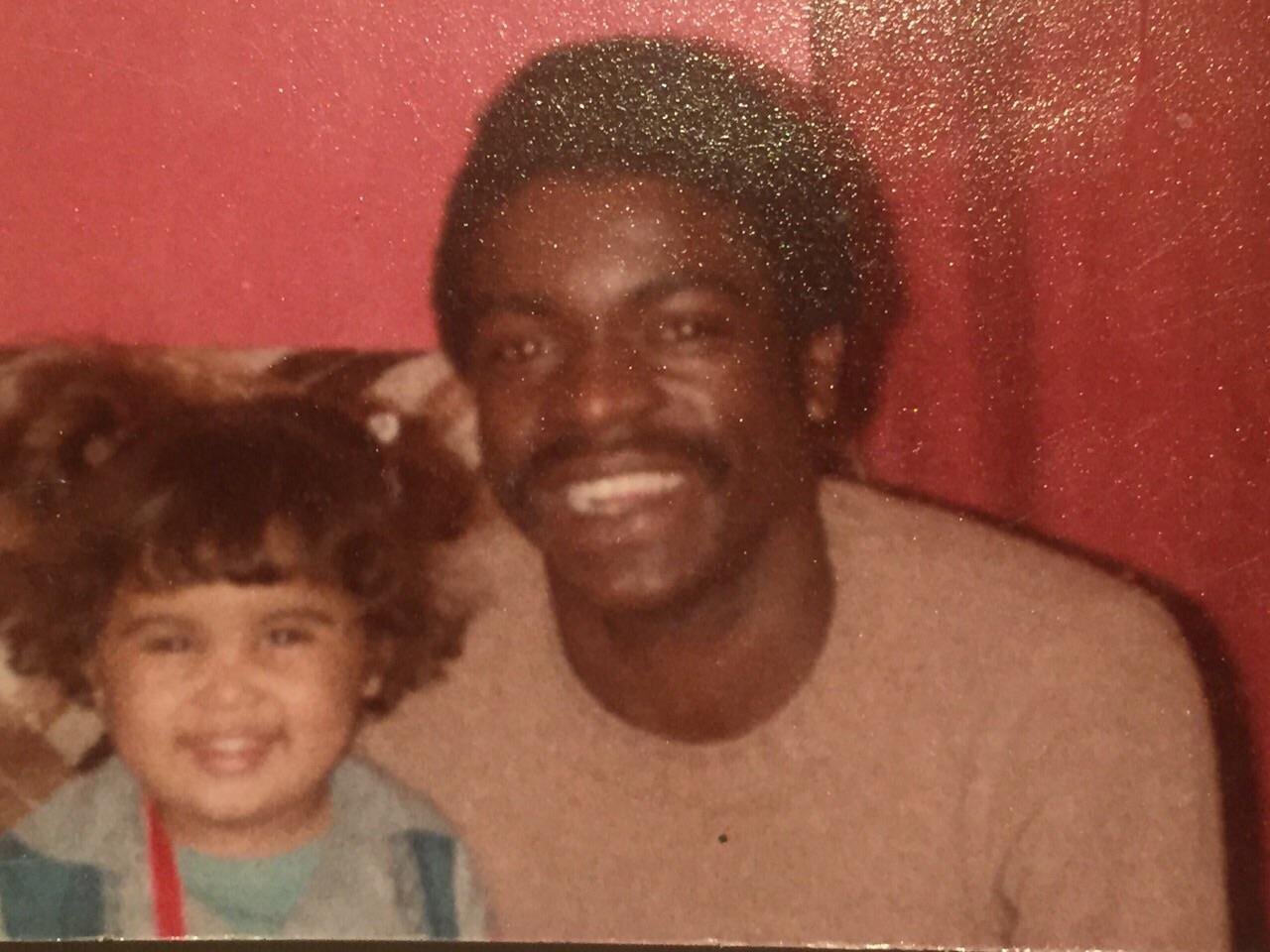

As time went on and I became more confident in who I was and how I looked, these feelings started to fade, but there were still regular comments about the size of my bum and people who’d comment that that I was ‘dark for mixed race.’ My mum, Mary was white and my dad, Ron was black and until then, I hadn’t thought any more of my cultural background and heritage. These experiences brought it to the fore.

Then, at the beginning of 2020 and pre COVID-19 lockdowns, I travelled to the Caribbean island of Montserrat with my husband Ross, 50, and our son Otis, four. This small island in the West Indies was where my paternal grandparents had grown up, fallen in love and started a family before moving to England in the 1950’s. It had always held a fascination for me and now, I wanted to see it and share my thoughts with my nan Clarice, 89, who had grown up there before moving the the U.K.

I wondered how Otis would cope with the long flight but I wanted him to understand more about his background, and mine. I also yearned to be able to speak to my nan, whom I was very close to, about the island. She’d told me so much about Monstserrat over the years and I was excited to finally experience it first hand.

It was even more beautiful that I’d imagined, with breath-taking landscapes, beaches filled with volcanic black sand and sunsets over deep blue waters that knocked you for six. Many mistakenly think it’s called the Emerald Isle because of those natural landscapes, but it’s actually due to the large Irish population that settled there in the 1600’s. It was another reason I wanted to see it. My maternal grandfather was Irish, and I’d heard stories for years how the island’s population doubled on St Patricks Day, with people flying in from all over the world for the week-long celebrations.

It was a bit of my cultural history I wanted to learn about.

Fitting in

But what I actually found in Montserrat was quite unexpected. Suddenly, I didn’t physically stand out. Nobody wanted to touch my hair, my skin colour wasn’t a trigger for negative assumptions or abuse, and for the first time in my life, I felt like my body was just fine - glorious, in fact. I didn’t feel that my boobs, bum, or thighs were too big and I didn’t feel self-conscious on the beach.

For years my mum and her sisters had prided themselves on being naturally slim. I didn’t have the same body type. Whilst this was no bad thing, during my formative years when I was bombarded with images of skinny, straight-haired white women, my curves felt like a negative – a bubbling reminder that I was different.

In Montserrat, everywhere I looked, I saw women just like me. There, my hair wasn’t too wild, and my skin was neither too dark nor too light. It was freeing. Usually, overthinking made it impossible for me to sleep without the aid of an app, but here, my racing thoughts dissipated with ease. For the first time in months, I slept without needing an app to help me switch off my mind.

During out trip, I met up with my nan's Sister Melvy, who’s in her 70s, and spent time getting to know her family. Over traditional, delicious homemade food like coconut cake, Sorrell drinks and more, I heard her stories about the family I hadn’t grown up with. It felt like a jig saw puzzle coming together as I recognised streaks of my own personality from the very real characters of the stories Melvy told. I also saw my nan in her, which was comforting.

History

Together, we visited an amazing museum called the Hilltop Coffee House that had artefacts from the aftermath of the volcano that erupted in 1997, wiping out most of the capital, Plymouth. The museum told the story of Sir George Martin’s Air Studios, and showcased all the singers and artists who’d come to the island to record music, including Sting, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Dire Straits and many more. It surprised me that I hadn’t realised the musical link so many of today’s mainstream stars had to the island, and brought me an added sense of intrigue and pride.

The history of the island was fascinating, and I loved being able to go through the villages my grandparents grew up in, and walk the roads they had once travalled on. We even found the house my nan had lived in with her dad.

Life on Montserrat felt very different to life back home, not only because of the obvious natural beauty all around but the relaxed manner of the people and the low crime rate. It blew my mind that when we were due to return our car to the hire company, they instructed us to leave it unlocked at the airport with the keys inside, and they’d collect it later.

The beauty of the island was staggering, the laidback lifestyle relaxing, the almost non-existent crime enviable, but along with all that I was touched by sadness. Sadness that my grandparents had never been able to fulfil their dream of moving back there. My grandad died at just 38 in a house fire, leaving my nan a single mum to four small children in a country that was not her own. I found myself wondering what my connection to Montserrat would have looked like had my grandparents returned there.

Reconnecting

I returned from our trip not only more appreciative of my body but also with a greater appreciation of my grandparents and what they had sacrificed to come to post-war Britain as part of the Windrush generation. Not only had they given up the beauty and ease of human interaction Montserrat offered, they’d unknowingly given up the chance of the future they had dreamed of, and planned for, together.

Those 10 days gave me a greater sense of self, and helped me make peace with who I am. I also now feel far more at ease talking about race, something I didn't really speak about before. Weeks after our return, George Floyd was murdered in the USA by police officer Derek Chauvin and I wrote a Facebook post about my experiences as a woman of colour.

Before Montserrat, I would never have opened up publicly about something like that, but the response I received was phenomenal. I was grateful to be able to confidently be a part of that important and ongoing dialogue.

More people are starting to do the work to educate themselves around race and that is a good thing. I hope that Otis grows up in a world that is more accepting and open to learning about race and understanding different cultures. I hope that we are making steps to implement changes, not only about overt racism, but the internalised racism and prejudice that we often can't even see in ourselves, but may be underlying due to years of ignoring parts of history or claiming ‘not to notice colour.’

My trip to Montserrat changed me for the better. I went there wanting to learn about my family but amongst its beautiful tapestry of culture and life, I ending up finding myself.

Like this article? Please help us commission more like it by donating the cost of a cuppa on Ko-fi. Sharing this article on your social media, and following us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are also a great way to support our independent, self-funded platform.

We encourage debate, but trolls are not welcome. Please read our comments policy before contributing.